Cosi (1996) and Looking for Alibrandi (2000), though disparate in plot, character, setting, and execution, share several attributes in common. Both are Australian comedy-dramas released within a five-year stretch. Both feature soundtracks of popular music, albeit the popular music of the 1700s in Cosi’s case. Both feature Greta Scacchi and Kerry Walker, though The Home Song Stories also featured the latter, which I guess makes this Kerry Walker Month on Down Under Flix. Both were adapted from sources originating in 1992—Cosi a play by Louis Nowra, Alibrandi a novel by Melina Marchetta—and their source authors also served as screenwriters. Finally, both of those source texts were, at least in my school years, part of the Victorian curriculum. I studied Marchetta’s novel prior to the film’s release, so was deprived of the ritual of watching it on a large television wheeled into the classroom. I was afforded that pleasure, however, for Cosi.

Directed by Mark Joffe (Spotswood), Cosi revolves around Lewis (Ben Mendelsohn, reuniting with his Spotswood director), who is hired to direct a performing arts show featuring patients at a mental hospital. One of those patients, Roy (Barry Otto), is zealous in his aspiration to stage Mozart’s Cosi Fan Tutte. The film follows Lewis, Roy and company’s madcap attempts to stage the production (the irony of Mendelsohn staging Mozart), and said company is, casting-wise, a true embarrassment of riches. In addition to Mendelsohn and Otto, the stacked cast includes Toni Colette, Jackie Weaver, Pamela Rabe, and David Wenham as performing patients, with Rachel Griffiths, Aden Young, and Colin Friels rounding out the ensemble.

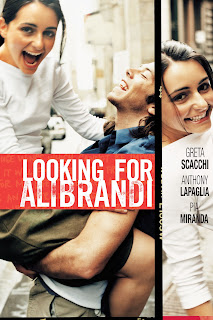

Looking

for Alibrandi centres on Josie (Pia Miranda), a teen of Italian descent raised by her single

mother (Greta Scacchi). The film chronicles Josie’s final year as a scholarship

student at a prestigious Catholic high school and the major life events of said

year, including meeting her long-absent father (Anthony LaPaglia, a few years

after Richard Franklin’s Brilliant Lies and kicking off the export

actor’s run of headlining Australian films), a budding romance with Jacob

(Miranda’s future Garage Days co-star Kick Gurry), a not-to-be romance

with John (Matthew #cancelled Newton), and coming to better understand her

overbearing grandmother (Elena Cotta).

Critics and scholars of adaptation such as Robert Stam and Linda Hutcheon suggest it's undesirable for texts to be beholden to their sources, and that a little bit of infidelity goes a long way in translating literary and theatrical sources to film. Both Cosi and Alibrandi are, I would argue, smart and thoughtful adaptations of their sources to screen, preserving the spirit of said sources but also rearranging events, recognizing what to discard, what to interpolate, and how to use the storytelling potentialities of film to best effect. In Cosi’s case, concessions are made in updating the story from the 1970s to the 1990s, in the process eliminating its counter-culture and anti-war background. On the flip side, the film presents sequences that would not be feasible in a stage production, most notably a montage of auditions at the start of the film and a montage of the final performance of Cosi Fan Tutte at film’s end. In Alibrandi’s case, energy and spunk are added through the title character’s quippy voiceover—I suspect Clueless was an influence here—and lively soundtrack, which mixes then-current songs from bands like Silverchair and Killing Heidi with the odd Italian ditty and even a smidgen of classical: Newton’s entrance, incongruous with his current pariah status, is lovingly scored to Handel’s coronation anthem “Zadok the Priest” (among things that firmly time-stamp the film, it’s perhaps second to the line “Yeah, I can just imagine letting a Wog be Prime Minister”). Intriguingly, both films also amplify the comedic aspects of their source texts, injecting some extra goofy digressions in a very late 1990s, early 2000s Oz comedy way. For example, in Cosi we see Lewis’s dodgy and pretentious actor friend (Young) performing a dodgy and pretentious play, and there’s a subplot involving Wenham’s bogan pyromaniac breaking out of the hospital and into Lewis’s house.

Cosi was a modest success, and Nowra won that year’s AFI Award for Best Adapted Screenplay (he would be nominated again shortly thereafter for adapting his play Radiance, and among subsequent screen credits he has an unlikely story credit on K19: The Widowmaker). Alibrandi was a more palpable success in what was, looking back, a pretty strong year for popular Australian film, also boasting the likes of The Wog Boy (a companion piece of sorts that similarly showcases the Mediterranean migrant experience), Chopper, and The Dish. Alibrandi reaped almost twice its budget commercially (no small feat for most Australian releases then or now) and won five AFI awards for Best Picture, Adapted Screenplay, Editing, Actress for Miranda, and Supporting Actress for Scacchi. The wins for Editing (Martin Connor, Burning Man) and former soap star Miranda were especially deserved: Miranda‘s wonderfully expressive and is assured with both the comedic and dramatic material the role presents.

Alibrandi director

Kate Woods, who’s worked entirely in television before and since, delivered a

nimble feature debut with both technical polish and a big, outsized heart on its

sleeve. She and her crew, like the makers of The Last Wave, also make very effective use

of a variety of Sydney exteriors, adding considerable production value to the film. Woods

was also AFI-nominated in the Director category but lost to Andrew Dominik for Chopper.

Whilst consistent with the AFI's streak of awarding the direction on grungy crime films

(following gongs for Bill Bennett on Kiss or Kill, Rowan Woods on The

Boys, and Gregor Jordan for Two Hands), in retrospect the Dominik

win is a dubious victory for topical grime and hip nihilism.